How Easy Are Octave Leaps on Violin

Leaping across multiple strings is like jumping across a mountain creek – we normally don't want to get our feet wet (touch the middle strings). Let's continue with this hiking analogy.

A leap is basically a combination of a step (horizontal) and a jump (vertical). In a "step" there is always at least one foot in contact with the ground (because the back foot doesn't leave the ground till the front foot has landed). In a "leap" however, we spend some time totally in the air. Even though it might be possible to cross the water with one big step, we will certainly be able to go further and faster if we add that vertical "jump" component, leaping instead of stepping.

On the cello, the "jump" is our vertical spiccato bounce, while the "step" is our horizontal displacement to another string. Leaping, as indicated by the word itself, is easiest when done in the air, both for cellists and mountain hikers. In other words, crossing multiple strings that we don't want to touch (hear) is normally easiest when we can do it with the bow in the air.

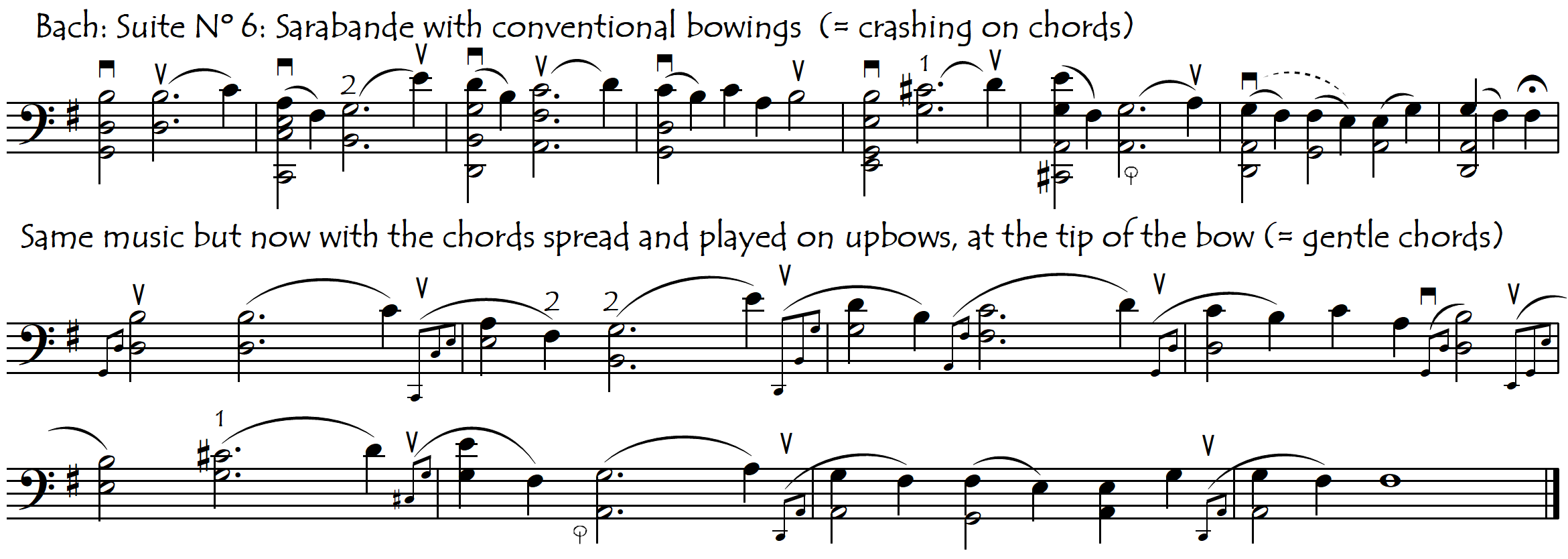

Sometimes however this is not possible, appropriate or even necessary. If we need to land with great delicacy and control, it will be normal to take a "step" rather than a "leap": we are very far from the world of spiccato here. This situation occurs commonly in legato passages involving chords such as in the Sarabandes from the Bach Cello Suites (here, the beginning of the Sarabande of the Sixth Suite). For more discussion of this, see "Crash Landings" at the bottom of the page and Chords.

There are several different factors that we need to look at when studying leaps across several strings:

- the speed

- the bow direction

- the characteristics of the departure: is it done with a bounce (jump) or not ? In other words, is the leap in the air [spiccato] or on the string [legato]??

- the characteristics of the landing: does it need to be smooth, soft, loud etc ??

If the take-offs and landings are all spiccato, and come on the favourable bow-stroke direction (see String Crossings and Spiccato) then we can be grateful: leaping across strings doesn't get any easier than this. Those spiccato leaps which come on the unfavourable bow direction are slightly harder, as here we are working against the natural tendency of the bow (leaping backwards is harder than leaping forwards).

As mentioned above, legato leaps are much more difficult than spiccato leaps as we can no longer leapfrog over the middle string(s) and thus have to "do magic" to avoid sounding them with the bow. If our bow direction is favourable this task is made slightly easier, but if the bow direction is unfavourable we are going to have to be very good at sleight of hand. The following examples illustrate these four different combinations of factors in increasing order of difficulty:

ADDING INTERMEDIATE NOTES IN LEGATO LEAPS

Most composers know that it is impossible to write a fully legato (slurred) leap across several strings. If a composer were to write the above excerpt with the leaps fully slurred this would reveal a lack of knowledge about how to write for string instruments. Brahms, when he wants some big legato leaps in his E minor cello sonata, carefully writes out the notes that he wants to sound on the middle strings during the legato crossing.

We could call these added notes "intermediate notes". They are like stepping stones, converting an impossibly wide leap across a river into several comfortable hops. They have a similar function to the intermediate notes that we often use in shifting: helping to make a difficult transition easier. But composers are not always so "user-friendly". More often than not, they don't write out these string crossing intermediate notes, simply because they don't understand the mechanics of string playing. How can a (non-cellist) composer really know if a big leap that he writes will be done as a shift to the adjacent strings or as a leap across a middle string obstacle ? This is asking too much.

Composers write the sounds they want to hear but it is up to the playing musician to decide how to achieve these sounds in the best way possible. Therefore, when faced with a difficult or impossible slurred or legato leap, we cellists may want (or need) to take the liberty of doing the same as Brahms did in the above excerpt: discreetly adding the notes on the middle (intermediate) string(s) that fit into the harmony. This will make our string crossing leap easier, which usually makes the music sound better also.

Having decided which intermediate notes to play (they need to fit in with the harmony) we then need to decide where to place them (rhythmically). Here we have two possibilities:

- between the original outside-string notes, and thus played like grace notes (as in the above excerpt)

- simultaneously with either the starting or destination note (or both) thus producing a double stop with the intermediate note(s) on the middle string(s) as in the following excerpts.

Even when the leap is not slurred, we may still want to make use of the intermediate note(s) simply to make the leap less "traumatic" even though it may not be strictly necessary. This is especially helpful when the leap comes on the unfavourable bow direction and not only makes the leap easier (no longer a leap in fact) but also allows us to slur the crossing should we wish for a more legato articulation:

CHOICE OF LEAPING STYLE: LEGATO OR ??

Sometimes, the presence of big leaps across strings is almost proof that the composer didn't imagine the passage played legato. This is especially so in Pre-Romantic music where the natural bowing was not in fact legato and composers used dots only exceptionally, to indicate the very shortest notes. When we play the Prelude to Bach's Fourth Cello Suite with a legato bowing style – as many people have done and still do – we are creating a lot of problems for ourselves (and for the music) because those leaps across 4 strings are basically impossible to do cleanly and simultaneously legato. Even such a magnificent cellist as Danil Shafran suffers a lot, regularly touching the middle strings with his bow and thus sounding undesired "parasite" notes that don't fit in with the harmony. In the days of Bach, the cellist would no doubt have played this piece with quite separated bow strokes, with the legato effect coming mainly from the echo in the church acoustics. If we want the same effect nowadays in a dry acoustic, we could always use the above "addition of double-stops" trick to simultaneously facilitate the legato string crossings and add resonance and harmonic richness.

To see the whole Prelude written out in this way, open the following link: BACH: SUITE Nº 4: PRELUDE WITH DOUBLE STOPS

TO LEAP OR NOT TO LEAP? FINGERING CHOICES.

We often have a choice as to whether we finger a large interval either across the strings (with a bow leap) or to a neighbouring string (with a shift or double extension). In this way we can displace the "difficulty" between the right and left hands at will: leaping across strings is a bow difficulty while playing the large interval on neighbouring strings is a left-hand difficulty. For a large legato interval we will normally try and shift to the adjacent string as this allows us to really connect the notes. But at other times the choice may not be so clear. This situation is especially common for passages in octaves. How would we finger the following passage for example ?

Our fingering choice here is determined principally by the speed. If the passage was to be played at a moderate tempo we could play the passage spiccato (starting up bow)with leaps back and forth across 3 strings, with the left hand staying in First Position. But the high speed at which we actually need to play it makes these bow leaps impossible. Therefore we need to use the thumb and play the octaves on adjacent strings.

Here is another Beethoven Sonata example of a passage in octaves for which we also need to decide "to leap or not to leap ?"

In this passage however, the tempo is slower so we now have enough time to play the octaves leaping across the 3 strings. What's more, the melodic line moves around so much that playing this passage "in octaves" (on only 2 strings and with the use of the thumb) would be very difficult. The bow leaping is made easier if we use an up bow on the lower notes. With respect to the rhythmic pulse, this is a "reverse (or "backwards") bowing because the accents (beats) come on the up bows (and we would need to take the last 2 semiquavers on two upbows). But with respect to the bow's bounce and mechanics, it is an ideal bowing. We can experiment and see which one suits us – and the music – the best.

BOW FOR THE BEAT OR FOR THE LEAP?

In the above example, the ideal "bounce bowing" (starting upbow) is not the same as the ideal "beat bowing" (starting downbow). However because this passage is not fast, our reverse bounce is not going to be such a problem and we might therefore choose to favour the accents by starting on the down bow. But let's imagine now that Beethoven had written the following:

Here the best bow direction for the rhythmic accents coincides with the best direction for the bounce so there is not the slightest doubt about which bowing to use.

LEAPS AND SLURS

If these octave leaps were slurred, leaping would be out of the question and we would have to use the thumb, fingering the octaves on adjacent strings, as in the following passage from Beethoven's Triple Concerto. The slur eliminates the possibility of using bow leaps across the strings and obliges the cellist to play the entire passage in octaves with the thumb – a virtuoso technique much more appropriate to the world of the "concerto" than to the world of sonatas.

CONTROLLED LANDING OR CRASH LANDING AFTER A LEAP

It is very difficult for a gymnast to do a gentle controlled landing after a spectacular aerial manoeuvre. We have the same problem with our bow after a big fast leap. To say the same thing with other words, fast leaps across several strings pose special problems when we need to do a soft landing, especially when we are landing at the frog or the lower half of the bow. When chords ornament a melody on a top string (as occurs so often in the solo string music of Bach), it is so much easier to hit the bottom notes of the chord hard than to play them gently. This is why the chords in Bach are often played dramatically and energetically even when the music wants to be gentle.

There are several solutions to this problem.

- don't leap: take a gentle, slow step (in which the bow stays on the string or at least very close to it); this is much easier to do at the tip of the bow than at the frog

- spread the chords: this allows us to start them gently.

These "anti-crash" techniques are especially appropriate for the Sarabandes. Try the Sarabande of Bach's Sixth Suite like this (2nd example) to see how it gains in gentleness, delicacy and ease of control:

PRACTICE MATERIAL

For more study (practice) material, open the following pages:

String Crossing Leaps Across 3 And 4 Strings: EXERCISES REPERTOIRE EXCERPTS

Source: https://cellofun.eu/home/cello-blog-encyclopaedia/mechanics-technique/right-hand-string-players/string-crossings/string-crossings-leaps-across-three-or-four-strings/

0 Response to "How Easy Are Octave Leaps on Violin"

Post a Comment